Animated feature films have come a long way since Walt Disney’s 1937Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. For films in the past two decades, the technical advances of animation are rivalled only by the increasing depth of storytelling.

Like many children and parents in Hong Kong and abroad, our family recently watched and loved the movie Inside Out. The plot is centred on an 11-year-old girl’s move to a new city and school, and contains plenty of entertaining flashbacks. However, her anthropomorphic emotions are the stars of the show, and they are created with colours that sensibly match each of them well: red for Anger, green for Disgust, blue for Sadness, purple for Fear and yellow for Joy.

Despite Inside Out being my five-year-old daughter’s second-ever movie experience, she managed to follow the storyline and even gain a better understanding of it than I expected. I was amused to hear her refer to the film when my elder one got testy about something. My daughter observed her big sister’s bad temper and stated, “Oh, she’s letting Anger take control at the front.” Ironically, her big sister’s takeaway from the film was apparently more superficial. For the past month, the only time she mentioned the film was when she asked to be dragged around our home by her ankles, just as Joy dragged around Sadness in the film.

This film is an ingenious way to help children learn that what one says is not necessarily a literal expression of what one is thinking or feeling, including they themselves. Understanding others’ intentions, and feeling compassion and empathy for others as a result of such understanding, are both big milestones in a child’s emotional development.

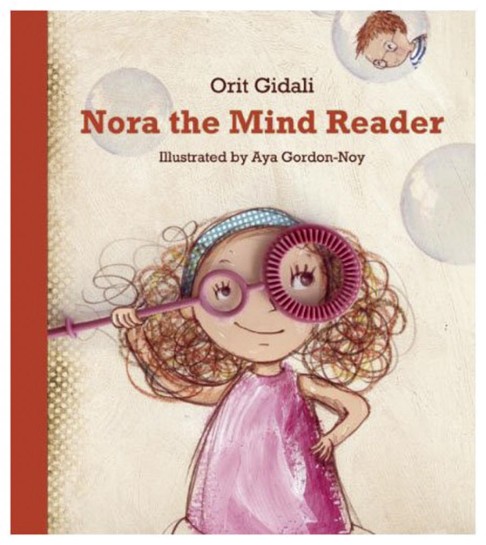

After seeing Inside Out, I couldn’t help but compare it with Orit Gidali’s picture book Nora the Mind Reader. A wonderfully inventive story that explains the nuances of communication to younger schoolchildren, it is translated from Gidali’s original Hebrew, and is complemented by delightful mixed-media-collage illustrations.

When Nora comes home from school in an unhappy mood because a boy has called her “flamingo legs”, her mother gives her a magic wand. Shaped like a bubble-blowing stick, the wand enables Nora to read people’s minds when she peers through its circles. Nora takes the wand to school and begins to witness how thoughts and words can sometimes be very different.

For children in middle school to be aware of different perspectives, Rob Buyea tells an inspiring story with different narrators in Because of Mr Terupt. The new school year begins with the arrival of a new teacher, Mr Terupt. Seven of the fifth-graders in his class take turns narrating the story about this teacher’s special ability to grasp the intentions behind these students’ words and actions. These seven children have different backgrounds and distinct voices, which lend themselves to original storytelling when the plot thickens.

Stories help us learn about other people’s lives. The bonus that comes with great children’s literature is that such stories provide evocative language, vocabulary and descriptions, which we can then use when we want to express what is inside our head. When we convey our intentions and verbalise our thoughts in a clear and concise way, people who hear what we say or read what we write will understand us without confusion or frustration on either end. Ultimately, that’s what most of us want from life: to be understood by others, and to make connections with others.

Annie Ho is board chair of Bring Me a Book Hong Kongbringmeabook.org.hk a non-profit organisation advocating family literacy